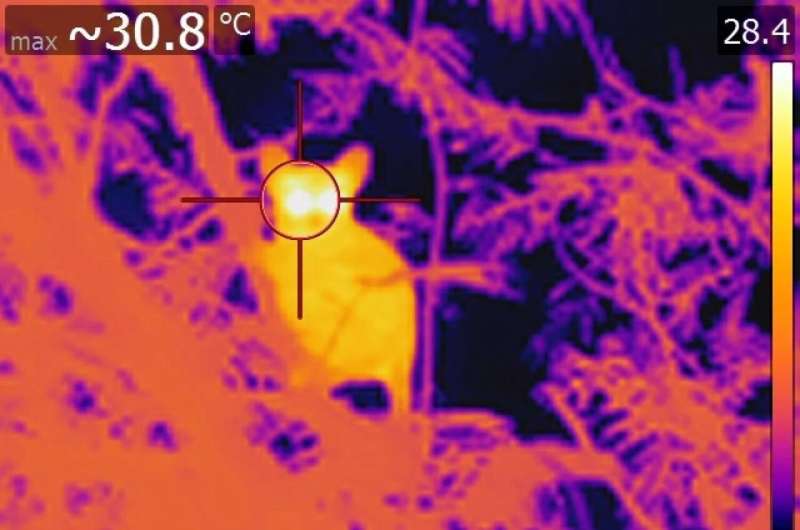

A galago was observed at night using a scientific thermal imaging camera. Credit: Michelle Souther

In the “sky islands” of South Africa’s Soutpansberg mountains, two closely related primate species fight for space. One is the greater thick-tailed galago ( Otolemur crassicaudatus ), also known as the bush baby, which is the size of a large cat and known for its high-pitched, wailing cry. The second primate, the lesser southern galago (Galago moholi), has large ears and eyes and is small enough to fit in the palm of your hand.

In new research, a team led by CU Boulder primatologist Michelle Sauther turned to these animals to explore an overlooked question in conservation: Being big or small changes how a animal in extreme temperatures?

The group’s findings suggest that small animals like the lesser galago could face additional challenges as the planet’s climate continues to change.

“Body size really affects everything,” said Sauther, a professor in the Department of Anthropology. “How big you are affects your life history. It affects when you reproduce. It affects how long you live.”

She and her colleagues recently published their findings in the International Journal of Primatology.

The study highlights the diversity of wild ecosystems at the Lajuma Research Center in the Soutpansberg Mountains. In this misty landscape, flowering plants and lichens abound, and annual temperatures can range from near-freezing in the winter to 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer.

Sauther and his colleagues set out in the dead of night to track greater and lesser galagos in the treetops. They discovered that maybe it doesn’t pay to be small. Lesser Galagos, unlike their larger cousins, seemed to have to forage in all weather conditions, even during periods of extreme heat or cold, giving them little respite from the harsh conditions.

For the primatologist, the study is another reminder that small animals also need protection.

“In conservation, we tend to focus a lot on lemurs, gorillas and chimpanzees,” he said. “But we also need to think about the implications of climate change for these smaller, nocturnal species, which most people don’t know much about.”

A tale of two primates

Think of the new study as a tale of two primates. On the surface, greater and lesser galagos appear to be remarkably similar: both spend their lives almost entirely in trees and are active at night when they hunt insects and lick gum from acacia trees.

But look a little closer and you can spot the differences.

“These guys look like they’ve had 50 cups of coffee. They’re bouncing all over the place,” Sauther said. “The older ones just seem to sit there and watch you.”

To find out how these animals divide the forests of Lajuma, she and her companions traveled the same paths through the reserve for 75 nights over a year. They looked for galagos by shining a red light on trees to detect glowing eyes, then observed the primates using a thermal imaging camera.

The team included James Millette, who earned a doctorate in anthropology from CU Boulder in 2016. Researchers from the University of Pretoria, the University of Venda in South Africa and the University of Burgundy in France also participated.

“At night, because you can’t see much, you start hearing all these things that you would never hear otherwise: lots of insects, lots of animal calls,” Sauther said. “Every once in a while, you’ll run into a leopard.”

However, when researchers weren’t dodging the big cats, a worrying trend emerged.

Greater galagos, the group found, tended to be awake and active during milder weather and were rarely outside in temperatures above 75 degrees Fahrenheit. The lesser galagos, on the other hand, were much more active in cold and hot weather. They could be seen jumping through the trees even when the temperature rose to 79 degrees Fahrenheit or dropped below 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Sauther suspects this disparity comes down to one thing: voracious appetites.

Like many small mammals, lesser galagos, which weigh only 150 grams, or less than an aluminum can, have fast metabolisms. That means they need food, all the time. Large galagos, on the other hand, can store more body fat, so they can afford to rest during extreme temperatures. The two species could also struggle to adapt as Lajuma warms further, Sauther said. He noted that none of the primate species are currently recognized as endangered, but they face increasing pressures from a range of factors, including the expansion of road networks across South Africa and trade of exotic pets.

She hopes the new study will inspire more research into these adorable, if hard-to-spot, animals.

“We’re concerned about these stealth changes that may be happening between species like these,” Sauther said. “We hear a lot from people: ‘I used to see them on my farm a lot, but now I don’t.’

More information:

Michelle L. Sauther et al, Environmental effects on nocturnal encounters of two sympatric Bushbabies, Galago moholi and Otolemur crassicaudatus, in a high-altitude montane habitat of the northern South African fog belt, International Journal of Primatology (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s10764-024-00427-5

Provided by the University of Colorado at Boulder

Summons: In South Africa, small primates could struggle to adapt to climate change (2024, May 7) Retrieved May 8, 2024, from https://phys.org/news/2024-05-south-africa -tiny-primates-struggle.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than any fair dealing for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Content is provided for informational purposes only.

#South #Africa #small #primates #struggle #adapt #climate #change

Image Source : phys.org